Summary

Next week, all eyes will be on the prime minister’s new roadmap out of national lockdown. The path and pace of that plan appear to be being driven as much by political pressure as they are by data and scientific advice.

Yet what the public wants is a clear, comprehensive and consistent plan to optimise health and economic outcomes, and return life to normal as quickly as it is safe to do so. The last exit strategy, which began in May 2020, conspicuously failed to achieve this. Case numbers accelerated through the autumn and a new, more transmissible variant of the virus emerged. Ultimately only the comprehensive national lockdown we are currently enduring has been sufficient to bring case numbers under control.

What lessons should we take from the missteps last time? The government made three critical errors in its approach to easing restrictions between May and October:

- There was no clarity on the government’s objective. That remains the case today, as evidenced by the fact that different cabinet ministers appear to disagree on whether scientific advisors are “shifting the goalposts”.

- There was no link between expert assessment of the state of alert and the suppression measures The Joint Biosecurity Centre’s (JBC) alert system has no relationship to the tiered restrictions later introduced. The lack of a link was central to the government acting too late to stop the second wave.

- The Treasury underestimated the economic implications of inadequate suppression of the virus. As a result we are now paying the price in the form of a severe second wave lockdown to contain a much more transmissible variant.

A better plan to emerge from lockdown this time should follow five steps:

- The plan must set out a clear policy objective – whether that be to prevent hospital overload, keep new cases below a given level or ensure that case numbers continue to fall. While any of these goals is plausible, in practice only a policy of keeping R consistently below 1 is likely to be deliverable.

- The government should ask the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M) to assess the likely path of the virus under its proposed exit plan and if necessary adjust the timetable to meet its own policy objective.

- Easing steps – and, if necessary, tightening – should be contingent on the data. For all the prime minister’s determination that steps out of lockdown should be irreversible, the paradox is that only a clear determination to take whatever action is necessary to keep case numbers falling can make that a reality. Therefore, at the heart of the plan, as TBI has argued since the early weeks of the pandemic, should be a clear framework of tiers of restrictions that are linked explicitly to the alert levels adjudicated by the JBC.

- Measures should operate at national, regional and local authority level. A rigid national or regional approach alone will involve unnecessary economic and social costs to contain the virus.

- Model the economic implications. HM Treasury should collaborate with SPI-M to develop and publish regular modelling on the interaction of the spread of the virus and economic activity under the government’s proposed plan and alternatives.

Once the vaccination rollout is complete, the degree to which life will be able to return to normal is very sensitive to the proportion of the population covered and the effectiveness of the vaccines in preventing transmission. While there are positive signs, it is far from clear that it will be possible to remove all restrictions without having in place a comprehensive containment infrastructure, involving digital health credentials, better incentives for self-isolation and widespread availability of rapid testing as TBI has advocated.

Introduction

After a gruelling winter lockdown, with Covid-19 fatality rates receding and vaccine rollout going better than expected, a weary country is looking to the government to set out its exit strategy.

As we wait to find out the government’s plans for how to ease restrictions, there are strong parallels with early May, when the government set in motion its path back to normality after the first wave of the pandemic.

Last time, though, the exit strategy didn’t work. Cases picked up in late August, arguably exacerbated by government policies, and the spread of the virus accelerated in September as educational settings returned. Government advisors sounded the alarm in mid-September but the policy responses that followed those warnings were weak. A new variant emerged in late September, which the relatively light November lockdown was inadequate to contain. As a result, a hard lockdown was required from the start of the new year.

The health and economic consequences of the failure to contain the virus over the past six months have been huge. Around two-thirds of the total number of Covid-19 deaths have occurred since September. The economy, running 6.5 per cent below pre-pandemic levels in October, slumped to 9 per cent below in November, and is likely now even further behind.

This time we need a better plan.

But this time things are different. There are many more reasons to be positive. We understand more about how the virus is transmitted and how to treat it, vaccine rollout is proceeding faster than almost anyone dared hope and should save lives and cut transmission, therapeutics are being developed and testing capacity is high.

But there are also reasons to be concerned. The “Kent variant” is far more transmissible than what we faced last spring and if it slips out of control the death toll could rise again. The economic recovery could be derailed if working-age people are cautious in the face of accelerating infections. Most worryingly perhaps is the fact that if cases rise again so too does the risk of further mutations rendering protection from vaccines or past infection ineffective.

In the face of such high stakes, how can we extricate ourselves from this lockdown without repeating the experience of the past six months? To get it right this time and to manage what will be an uncertain situation for the rest of the year and perhaps beyond, we need to start by exploring what went wrong last autumn.

What Went Wrong?

Endless column inches have been filled with commentators chronicling the many policy failures of the government’s pandemic response over the past year. NHS Test and Trace was not ready to play a significant role in containing the virus either through conventional means or via the contact-tracing app, and mask-wearing became mandatory only after weeks of prevarication. Furthermore, despite substantial improvements in testing, the capacity of the system came under huge strain in early September. The wider public communications and associated policies also left a lot to be desired, not least the Dominic Cummings affair and the controversial Eat Out to Help Out scheme. In late August ministers launched a “back to the office” drive that was swiftly reversed as case numbers accelerated.

But in this report we focus on the government’s approach to lifting – and then reimposing – restrictions on social contact. We explore what went wrong and what that means for the forthcoming strategy to release the country from the current lockdown.

At the most basic level, the answer to the question of what went wrong is obvious: The government was too slow in the autumn to take measures sufficient to halt the acceleration of the virus. What lay behind this tardiness were three overlapping problems.

First, there was no clarity on the government’s objective. Was the government’s aim to keep the number of cases from rising (i.e., to keep R below 1), or to keep fatalities and cases below some tolerable level, or perhaps to allow the virus to spread but shield the most vulnerable, as some advisors proposed? Ultimately the strategic confusion about the government’s aim meant they achieved none of these goals.

This lack of clarity was reflected in the blizzard of confusing metrics that the government had established to judge the pace of easing through the summer. Its 11 May exit plan spoke of five tests, including considerations like NHS capacity, PPE availability and the vague aspiration to be “confident that any adjustments to the current measures will not risk a second peak of infections that overwhelms the NHS”. At the same time, the government established a timetable for lifting restrictions, which appeared to contradict the contingent basis for reopening represented by the tests. Finally, the plan included a role for the newly established JBC to operate an alert system “to inform decisions to ease restrictions in a safe way”.

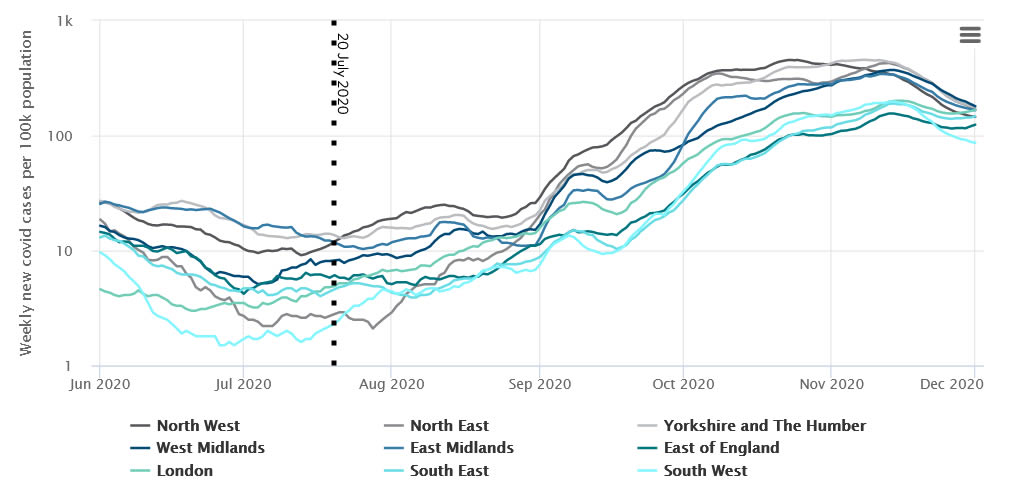

The consequences of that confusion were brutally exposed in the autumn. By late August case numbers were rising again, with the R number at or above 1 in all regions in the first half of September. While there were significant interventions in some local areas, measures to contain the wider spread of the virus were timid and ad hoc, at least until the tier system was announced on 14 October. Once the tier system was introduced, it was unclear why different areas were put into the tiers they were in. At the same time the restrictions involved in Tiers 1 and 2 were too weak to get the R number below 1, with formal studies and the government’s own subsequent assessment suggesting that only Tier 3 restrictions were sufficient to bring the virus under control.

Figure 1 – Case numbers rising in almost all English regions by early September

The second problem with the last exit strategy was that there was no link between expert assessment of the state of alert and the suppression measures taken. The JBC’s alert system was announced with some fanfare by the prime minister in May, but its advice was entirely unrelated the government’s actions. The JBC lowered the alert level from 4 to 3 on 19 June, and raised it again on 21 September. But neither event was accompanied by major changes in restrictions, making the alert system largely irrelevant to policy.

In October a more standardised regime of tiered restrictions was introduced, and subsequently revised in December. In terms of the JBC’s alert system, it has recently established a clear set of thresholds that guide its assessment. But there remains no link between the alert level and the prevailing tier of restrictions either locally or nationally. To date, Tiers 2 to 4 and lockdown have all been seen within the JBC’s alert level 4, suggesting that as currently set up, the alert system is not sufficiently granular to guide policy action. The fact that assessment and action have been divorced from one another was a central reason for the slow and inadequate response.

Figure 2 – Approximate alignment of alert levels and December tiers

The confusion about aims and the disconnect between advice and action was then compounded by the third shortcoming in the government’s strategy: It was operating on a partial understanding of the economic implications of the risks of inadequate suppression. Pressure from HM Treasury to delay or water down suppression measures appears to have been based on a view that such measures would be bad for the economy.

There is no doubt that, in the short run, tighter restrictions imposed earlier would have hampered economic activity in September and October. But the consequences for the economy of the surge in cases and deaths in the autumn resulting from a laissez-faire approach – not to mention the inevitable need for a tougher, longer lockdown subsequently – seem to have been discounted. In its November assessment of the economic effects of the spread of Covid-19, the government devoted just one paragraph to the economic damage caused by voluntary social distancing due to fear at times when the virus is prevalent. Had the Treasury assimilated the substantial body of research on this issue, it might not have underestimated the vast costs of erring on the side of inaction.

Figure 3 summarises the three broad areas in which the previous exit strategy came up short, and where we stand on these questions ahead of the government’s next exit plan announcement.

Figure 3 – Progress towards, and remaining gaps in, the strategy

| Area | Component of strategy | Spring 2020 | February 2021 |

| Policy clarity | Clear policy goal for case numbers and R? | No | No |

| Assessment linked to action | Alert thresholds defined? | No | Yes |

| Tiers of suppression measures specified? | No | Yes, October/December tier systems | |

| Tiers tied to alert levels? | No | No | |

| Economy | Modelling of virus and economy together? | No | No |

So a lack of clear policy, a failure to link assessment to action, and an inadequate understanding of the interaction between the virus and the economy conspired to allow a second wave, and with it the emergence of a new and more infectious strain.

A Better Plan

This time around, all three of those failings need to be rectified. A comprehensive strategy should consist of actions to take before easing begins and then a framework to guide decisions once it is underway.

Before Easing

1. Set a clear policy.

Unlike the exit strategy published by the government on 11 May, the forthcoming one needs to start by setting out a clear policy for what the government’s goal is. The chancellor is reportedly concerned about scientific advisors “moving the goalposts” on lockdown away from a goal of protecting the NHS and hospital admissions and towards one of focusing on cases. The division this created within the cabinet once again highlights the lack of a clear policy objective from the government: Rather than the goalposts having moved, it seems that different departments have been using different goalposts from one another since last May.

Articulating a clear agreed objective for the easing phase should not be difficult, but they must pick one. For example, the government could articulate an aim to move down the tiers of restrictions as quickly as possible consistent with:

- keeping case numbers on a stable or declining trajectory (keeping R below 1); or

- keeping daily case numbers below some specified maximum rate; or

- preventing NHS overload, perhaps measured by hospital admissions.

The strategy over the summer and autumn appeared to involve the goal posts shifting gradually from the first of these to the last. This time around they need to be agreed by the cabinet explicitly rather than having different departments defining and pursuing their own divergent aims.

Which of these policies is likely to be optimal? The third option – preventing the NHS being overloaded – appears to be the Treasury’s preference if reports about the chancellor’s views are to be believed. The Conservative Covid Recovery Group has also pressed for the lifting of all restrictions by the end of April once all of the priority groups have been offered the vaccine.

Lifting restrictions while most people are unvaccinated would likely lead to a rapid resurgence in case numbers. This would be risky for three reasons. First, there will inevitably remain several million vulnerable people who will not have had the vaccine for one reason or another, making it likely that we would see another spike in deaths and hospitalisations. Second, another wave of infections is likely to do significant economic damage if working-age people restrict their activity and social consumption out of fear, setting back the recovery. Third, another spike in infections increases the risk of further mutations or the spread of more resistant strains, cases of which are already in the country in small numbers.

The second option of keeping case numbers below some maximum level is too difficult to achieve, as the experience of the past year has shown.

The safe and practical option would be to commit to a policy of keeping the virus under control with case numbers steadily and continuously falling, at least until the entire adult population has been vaccinated. Below we consider some of the uncertainties around how quickly normality could return under this policy.

2. Is the easing plan consistent with the policy?

The government may want to sketch out a timetable for easing restrictions from early March. But it will be critical that the easing plan is consistent with whatever policy objective it sets: neither too slow, imposing unnecessary economic and social costs, nor too fast causing a resurgence. Achieving this consistency between plan and policy is even more complicated this time than it was in 2020 due to uncertainty around the impact of vaccines on transmission. The government should therefore seek the consensus view of SPI-M on the likely path of the virus under its plans and if necessary adjust the timetable to meet its own policy.

During Easing

3. Easing steps – and if necessary tightening them – should be based on tiers and contingent on the data.

At the heart of the plan, as TBI has argued since the early weeks of the pandemic, should be a clear framework of tiers of restrictions that are linked explicitly to the alert levels adjudicated by the JBC. This should be clearly set out and communicated to the public. By setting out the policy and framework for guiding what measures are taken, the government can secure public understanding of and adherence to changing rules during the coming period of uncertainty.

The prime minister has expressed his desire to make steps out of lockdown irreversible. Paradoxically, this will depend upon a clear-eyed willingness to act quickly and decisively to reimpose restrictions again if numbers suggest the government’s policy goal is off track.

There have been reports that the government intends to drop the use of tiers, on the grounds that they were not sufficiently effective to control the virus. This would be a mistake. If the restrictions associated with the December tier system were insufficient then they should be revised. In any case, the broad outline of a staged reopening is already clear: It will begin with schools and end with hospitality. But establishing a clear framework of tiers is important since it may become necessary to reverse course and tighten restrictions once again if the policy is in danger of not being met. Setting out a pre-planned approach to manage this uncertainty is far better than taking an ad hoc one if the plan goes off track.

Bringing the alert levels, tiers and associated restrictions together should allow the government to set out a clear framework that could look something like the table in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – A framework for a system of linked tiers and alerts

4. Measures should operate at national, regional and local authority level.

The prime minister has floated the possibility of dispensing with locally targeted restrictions once lockdown is lifted. And it is clear that the local approach to restrictions failed to contain the second wave last autumn.

However this would be a mistake. The failure of local and regional interventions during the autumn was primarily due the government’s unwillingness to impose sufficiently strong and timely measures in local areas. Indeed, by the end of September, new case rates in three entire regions of the country were above the levels seen in Leicester at the end of June, when tough restrictions were imposed, yet the containment effort in September was weak by comparison.

Not taking a locally targeted approach to containment this time would make it far more costly to take decisive action to tackle local flare-ups, since the economic and social price would be paid by the whole country. A rigid national approach would therefore make it highly likely either that the virus would slip out of control or the economic and social costs of excessive restrictions in some areas would be unnecessarily high.

Rather, an effective strategy should allow for both regional and local variation in restrictions, operating on the basis of the same pre-determined set of thresholds and tiers as the national policy described above. These too should be adjudicated by the JBC.

5. Model the economic implications.

The final underpinning of a successful exit strategy is to ensure that it is guided by modelling of the virus and the economy together. A critical failure in the last exit strategy, as outlined above, was the Treasury’s apparent reluctance to consider the counterfactual path of economic activity if the spread of the virus continued to accelerate. While any such assessment has to be made under a huge amount of uncertainty, recognising the fundamental interaction between the virus and the economy should be at the heart of economic policymaking during the exit phase, as last week’s House of Commons Treasury Committee report, drawing on TBI proposals, made clear.

One way to achieve this quickly would be for the government to ask its epidemiological modelling advisors in SPI-M to estimate the rate of spread of the virus under different easing timetables. HM Treasury or the Office for Budget Responsibility could then set out their view of what those forecasts may mean for the economic recovery based on the growing evidence about the effects of the virus on voluntary social distancing. This would allow the government to optimise the timing of reopening: Maintaining restrictions too long would create an excessive drag on economic and social activity, while releasing too early could cause a resurgence in the virus that halts any recovery as people reduce social consumption out of fear.

After Vaccination Is Complete – How Normal?

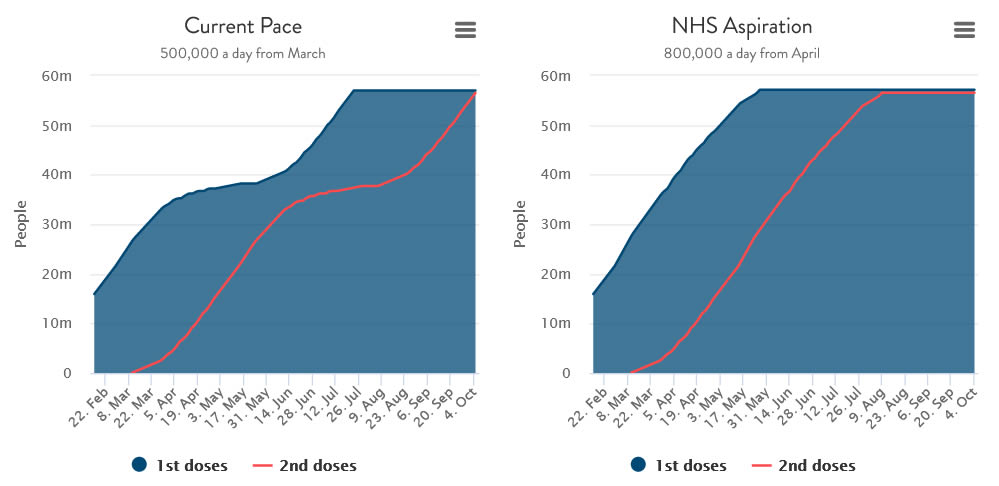

The above strategy should be followed until the vaccine is fully rolled out. A huge amount of progress has been made in distributing jabs since the start of the year with approximately 430,000 doses being administered each day. But there remains a long way to go before the entire adult population is protected.

The decision to increase the period between first and second doses of the vaccine has massively increased the number of people who are able to receive some protection quickly. Nevertheless, once the time comes due for second doses to be administered, this quickly begins to eat up delivery capacity. Based on the doses given out to date, if we assume that vaccination capacity edges up to around 500,000 per day in March, first-dose rollout hits a wall from the start of April and only begins again in earnest in June once all second doses have been given (see the first chart in Figure 5). This implies that under-50s can probably only expect to receive their first dose in June or July.

However, on 15 February the NHS Chief Executive Sir Simon Stevens expressed his aim to double current rates of vaccination. This would remove the “first-dose wall” in April and May and allow all adults to have been offered the vaccine by late spring.

Figure 5 – Timing of vaccine rollout under current pace versus NHS aspiration

So vaccine rollout could be completed much sooner than anyone dared hope, and in the meantime easing restrictions in a way that keeps R below 1 is likely to be the optimal policy from both a health and economic perspective over the coming months. But what happens then?

Whether the vaccine programme will allow the removal of all remaining restrictions without triggering a spike in cases depends on the effectiveness of the vaccines at preventing transmission and the proportion of the population covered.

On transmissibility, a recent study of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine concluded it reduced positive swab tests by 67 per cent among people who had received a first dose compared to a control group, suggesting similar or perhaps even higher reductions in transmission. And a recent Israeli study found that among vaccinated people who nevertheless became infected, the viral load was substantially reduced, perhaps lowering their chances of passing on the virus. Meanwhile, on the likely level of vaccine coverage, a recent ONS survey found that 92 per cent of UK adults appear willing to be vaccinated, with just 3 per cent saying they would be unlikely to accept a dose.

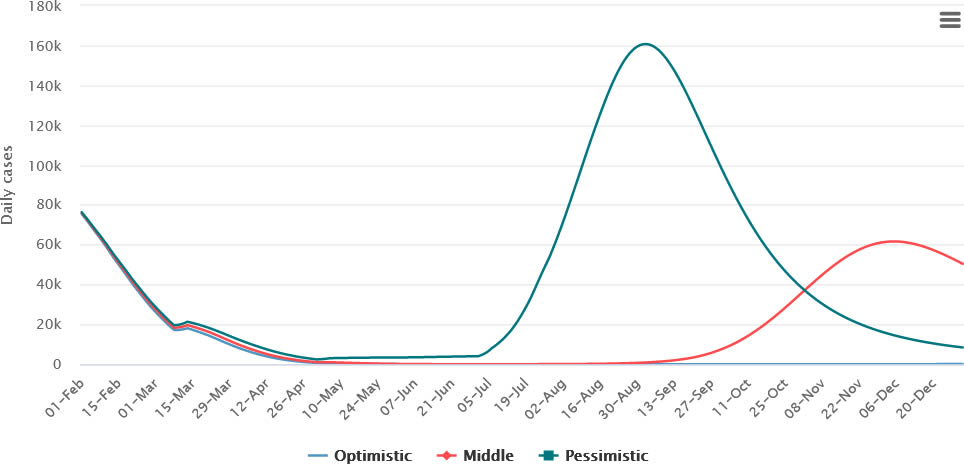

These are encouraging figures, but whether the vaccination programme will end the epidemic and allow the removal of most or all restrictions is finely balanced. Using the TBI Total Covid Cost Model, it is possible to get an idea of just how sensitive the risk of a future outbreak may be to the coverage achieved by the vaccination programme and vaccines’ effectiveness at reducing transmission. The scenarios should be taken as illustrative only.

- On the optimistic projection presented in Figure 6, 85 per cent of the population have had at least one dose by the summer, and the vaccines are assumed to reduce transmission by 80 per cent. This allows all restrictions to be lifted at the start of July with case numbers continuing to fall as R remains below 1.

- The middle scenario looks at what happens if both coverage and the transmission impact are slightly lower. It assumes 80 per cent of the population take up the vaccine but that it reduces transmission by 75 per cent. The result is a limited resurgence of the virus in the autumn with no restrictions, and assuming no significant improvement in containment measures.

- On the pessimistic scenario, vaccine coverage reaches just 75 per cent of the population, and vaccines reduce transmission by only 70 per cent. On these assumptions, lifting all restrictions results in a large spike in cases in the autumn of comparable size to the recent peak, albeit the consequences of such a wave in terms of fatalities would be much reduced.

Figure 6 – Three scenarios based on projections of vaccine coverage and effectiveness at reducing transmission

This suggests that the degree to which normality can return after vaccine rollout is very sensitive to things that we don’t yet have a clear understanding of, and won’t for some time. It seems likely that the scope to lift remaining restrictions in the summer will depend upon the effectiveness of the accompanying containment infrastructure. As TBI has argued elsewhere, there is much to be done.

- As Tony Blair has argued, it is likely that some form of health credential – conveying a person’s vaccination status or the result of a recent test – will be required for many forms of social consumption and international travel to resume in earnest without infections accelerating. With the UK hosting the G7 this summer, the government has an opportunity to coordinate a common set of standards for taking this idea forward.

- Recent statistics from the NHS Test and Trace programme are significantly improved compared to the autumn, with the central operation coordinating better with local authority experts, and higher proportions of contacts reached faster than before. In the latest data the median contact was reached within 78 hours of a case reporting symptoms compared to around 120 hours in the autumn. The app, too, appears to be reducing transmission, with a recent study suggesting it has prevented 600,000 cases since it became available. Nevertheless, problems remain, particularly around people avoiding getting a test when they suspect infection and around one in five of those asked to isolate failing to comply. Better sick pay and other more direct financial incentives to isolate are critical parts of the solution. For example, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) recently estimated that fully 70 per cent of applications to the £500 self-isolation payment scheme have been rejected.

- Finally, the need for widespread rapid testing may well increase, particularly if vaccination leads to more asymptomatic infections that could nevertheless be passed on.

Together with mass vaccination these containment measures, if properly implemented, offer a path back to near normality within months. The need for vigilance and government willingness to respond decisively to future adverse developments will, however, remain.